Details

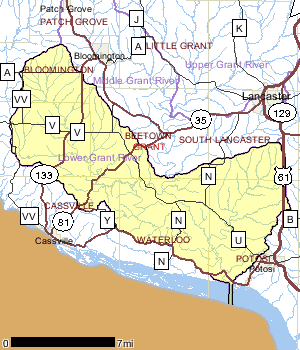

The Lower Grant River Watershed is a 145 square mile watershed in southwest Grant County. It includes the mainstem of the Grant River from its mouth at Pool 11 on the Mississippi River upstream to Pigeon Creek. Other principle streams in the watershed include Rattlesnake Creek, Boice Creek and Muskellunge Creek. The watershed contains approximately 66 miles of warm water sport fishery.

Land uses in the watershed are mostly rural and agricultural land accounts for roughly 86 percent of the 130 square mile drainage area. About 62 percent of the watershed is cropland. Woodlots occupy another 12 percent of the watershed.

The most extensive grouping of wetland complexes in the watershed are in the lower reaches of the Grant River where it empties into Pool 11 of the Mississippi River. There are other smaller wetlands adjacent streams in the watershed. These wetlands are usually grazed. Many acres of wetlands adjacent streams are farmed. Farms in the watershed are relatively large, with an average farm size of 310 acres (Bachhuber et.al., 1991). Corn is the dominant crop grown and livestock operations include a mix of dairy, beef and swine.

Date 2001

Population, Land Use

The topography is gently to moderately rolling land with steep-sided valleys and broad ridge tops. In certain areas, bedrock outcroppings are readily visible on the stream bottoms and along the stream corridors. Agriculture makes up approximately 90 percent of the land cover. Generally, 55-70% of the landcover in the subwatersheds is in cropland while 21-25% is in pasture. While the hilltops are generally cropped, the stream valleys are pastured and the highly agricultural landscape and steep slopes lend themselves to delivery of high sediment loads to the streams that drain the valleys.

Bank erosion is a major problem in the watershed. The steep gradients of the streams prevents buildup of sediment in the streams themselves save for the deeper pools, but the problem is moved downstream to larger, lower gradient systems like the lower Grant River and the Mississippi River. The Grant River has historically carried one of the highest sediment loads in the state, which can be evidenced by the delta of eroded sediments that has developed at the river?s mouth (WDNR, 2001).

There are no incorporated areas in the Lower Grant River Watershed. The unincorporated community of Beetown is in the watershed. It is estimated that about 2,600 people live in the watershed (Bachhuber et.al., 1991). Public access to streams is limited to road crossings. Hunting is allowed on private lands with the permission of the property owner. Increased participation in the CRP and CREP programs would increase wildlife habitat in the watershed.

Date 2012

Nonpoint and Point Sources

Nutrient enrichment has been a problem in these watersheds. In the late 1980?s, dissolved oxygen levels approaching 0 mg/l were reported following rain events and subsequently resulted in fish mortality (WDNR, 1991). The nutrient enrichment is also evident in the enhanced numbers of fish, particularly omnivores, present in a system. Biologists noted that, in conducting these shocking surveys, it was impossible to capture the shear biomass (numbers of fish). Despite capturing hundreds and even thousands of fish at some sites, biologist estimated that they were only successful in capturing one-third to one-half of the fish present in many of the surveys. The nutrient loads enhance algal and periphyton growth, which then enhances available food for grazers and this pattern is repeated up the food chain. Contrary to the conventional thinking that more fish equates to a healthier system, the enhanced abundance of fish is actually a sign of nonpoint source pollution impact, and while these streams may not necessarily be considered as impaired, it does indicate excessive eutrophication of these systems.

The Lower Grant River Watershed was selected as a Wisconsin non-point source abatement priority watershed project in 1989. It is scheduled to end in October of 2001. The priority watershed project is a partnership of the Grant County LCD, the DNR, DATCP and the NRCS. These agencies work together with willing landowners in the watershed to install non-point source best management practices to protect water resources and improve farm conservation practices. Goals of the priority watershed project are to:

improve sport and forage fish populations;

reduce organic pollution from livestock wastes by 75 percent;

improve riparian habitat (Bachhuber et.al., 1991).

As of 1998, the watershed project had signed 71 contracts in the watershed to improve water quality. The project has provided over $700,000 in total cost sharing to protect and improve water resources (Grant County, 1998). Participation by landowners in the watershed project, however, has been less than desired. This is reflected in the reductions of barnyard phosphorus and streambank erosion that are significantly below expectations. As of 1997, only 10% of the total barnyard phosphorus loading reduction desired had been accomplished. Sediment loading reductions from streambank erosion were at less than 10% of desired goals. By contrast, it was projected that the goal for upland sediment reduction or soil loss would exceed its goal (DATCP, 1998).

Date 2012

Ecological Landscapes

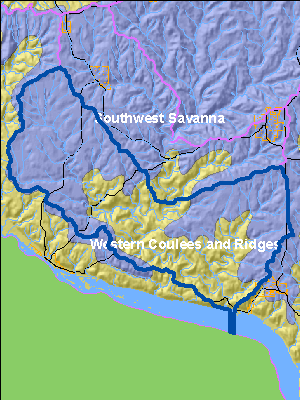

The Lower Grant River Watershed is located in two ecological landscapes.

The Southwest Savanna Ecological Landscape is located in the far southwestern part of the state. It is characterized by deeply dissected topography, unglaciated for the last 2.4 million years, with broad open hilltops and river valleys, and steep wooded slopes. The climate is favorable for agriculture but the steep slopes limit it to the hilltops and valley bottoms. Soils are underlain with calcareous bedrock. Soils on hilltops are silty loams, sometimes of shallow depth over exposed bedrock and stony red clay subsoil. Some valley soils are alluvial sands, loams, and peats. Some hilltops are almost treeless due to the thin soil while others have a deep silt loam cap.

Historic vegetation consisted of tall prairie grasses and forbs with oak savannas and some wooded slopes of oak. Almost three-quarters of the current vegetation is agricultural crops with lesser amounts of grasslands, barrens, and urban areas. The major forest types are oak-hickory and maple-basswood. High-quality prairie remnants occur on rocky hilltops and slopes that are not farmed. Some prairie pastures and oak savannas still exist. The grassland areas harbor many rare grassland birds, invertebrates, and other grassland species. Relict stands of pine occur on bedrock outcroppings along some stream systems.

The Western Coulee and Ridges Ecological Landscape is located in southwestern and west central Wisconsin and is characterized by its highly eroded, driftless topography and relatively extensive forested landscape. Soils are silt loams (loess) and sandy loams over sandstone residuum over dolomite. Several large rivers including the Wisconsin, Mississippi, Chippewa, Kickapoo and Black flow through or border the Ecological Landscape.

Historical vegetation consisted of southern hardwood forests, oak savanna, scattered prairies, and floodplain forests and marshes along the major rivers. With Euro-American settlement, most of the land on ridgetops and valley bottoms was cleared of oak savanna, prairie, and level forest for agriculture. The steep slopes between valley bottom and ridgetop, unsuitable for raising crops, grew into oak-dominated forests after the ubiquitous presettlement wildfires were suppressed. Current vegetation is a mix of forest (40%), agriculture, and grassland with some wetlands in the river valleys. The primary forest cover is oak-hickory (51%) dominated by oak species and shagbark hickory. Maple-basswood forests (28%), dominated by sugar maple, basswood and red maple, are common in areas that were not subjected to repeated presettlement wildfires. Bottomland hardwoods (10%) are common in the valley bottoms of major rivers and are dominated by silver maple, ashes, elms, cottonwood, and red maple. Relict conifer forests including white pine, hemlock and yellow birch are a rarer natural community in the cooler, steep, north slope microclimates.

Date 2010

Hydrologic Features

The terrain in the upper parts of the watershed has long gentle slopes of between one to five percent. In the remainder of the watershed, the slopes are steeper, often in excess of 20 percent. The steeper slopes lead to the more rapid runoff of stormwater and snowmelt. Consequently, the streams of the watershed tend to be subject to very rapid increases in stream levels during and immediately after runoff events. Soil erosion, a concern everywhere in the watershed, is particularly a problem in the areas with steeper slopes.

The watershed has an abundant supply of groundwater. Groundwater in shallow aquifers is the source of virtually all drinking water in the watershed. Two studies done in the watershed indicate that nitrate concentration in groundwater is a concern. A study done in the Rattlesnake Creek part of the watershed showed that 23.5 percent of the wells tested exceeded state standards for nitrates (University of Wisconsin, 1989).

Studies done in Iowa found a direct correlation between increasing use of nitrogen based fertilizers and increasing level of nitrates in groundwater. Overall, the groundwater in the watershed has been ranked as a high potential for groundwater contamination.

Date 2001

Fisheries

Most of the waters in these watersheds to be cool transitional waters; the coolwater IBI (Lyons, 2012) was applied to all streams. A total of 35 species were found throughout the watershed. White sucker, johnny and fantail darters, creek chub, common shiner, central stoneroller and bluntnose minnow were the most widely distributed species. Smallmouth bass were found at 21 of the 32 sites. Most species found were either coolwater transitional species or warmwater species (Ibid). Brown trout, a stenothermal coldwater species was found at 3 sites in limited numbers.

Qualitative habitat surveys showed most sites to be �fair� to �good� in habitat rating. A majority of stream sites had poor to fair buffer scores due to the prevalence of pasturing in stream valleys throughout the watershed. However, while many of the banks were noted as trampled, many remained grassed and thus the bank erosion scores were generally �good� to �excellent�. Many of the systems received good to excellent scores for riffle-to-riffle ratio, fine sediments, and fish cover owing to the good gradient of the streams in this area which allows for scouring of sediments and provides good riffle-run-pool complexes.

Date 2012

River and Stream QualityAll Waters in WatershedThe streams of these two watersheds have historically contained populations of smallmouth bass and a diversity of nongame species. While the Grant River itself was not surveyed as part of this study, it offers a source of species recruitment, a conduit for fish movement, and a refuge for larger fish during the winter and low water years. The tributaries to the Grant River contain a subset of its species assemblage. Rattlesnake Creek supports a fishable population of smallmouths as does Boice Creek albeit to a lesser extent. The other streams in the watershed are home to high populations of nongame species, but can also serve as nursery streams for smallmouth bass and provide an important role in maintaining healthy bass populations. Several small unnamed headwater streams, which are primarily spring and seepage fed, contained limited numbers of fish, not only due to their small size, but likely also because their water temperatures were too cold to be tolerated by the majority of species making up these watersheds.

This area has also been historically impacted by chronic nonpoint source pollution problems. The priority watershed project which took place in the early 1990�s documented flashy nature of these high gradient systems, the inherent erosion, and the large sediment loads being delivered from the Grant River watersheds. The priority watershed project conducted in the 1990�s was only partially successful at reaching the goals of sediment and nutrient reduction (WDNR, 2001).

Approximately 90 percent of the land use in these watersheds is in agriculture, either row crops or grazing. For the most part, conservation practices such as contouring and strip cropping are practiced throughout the watersheds. Spring melt and early season rains, especially before crops are of sufficient size to reduce rain impact, can greatly increase the amount of sediment and nutrients reaching the streams.

Date 2012

Watershed Trout StreamsWatershed Outstanding & Exceptional ResourcesRiver and Stream QualityAll Waters in Watershed The Grant River carries one of the highest sediment loads in the state, which can be evidenced by the delta of eroded sediments that has developed at the river's mouth. This high sediment load is a concern on more than just a state or regional level since the Grant River is a major contributor of sediment and nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) to the Mississippi River. Overall, the increased runoff, due to agriculture, over the last 150 years has affected instream water quality, habitat, and fisheries of streams in the watershed. In fact, the primary cause of water resource problems in the watershed is poor water quality, specifically low dissolved oxygen following runoff events (Wang et.al., 1996). Department studies indicate that the cause of the low dissolved oxygen levels appears to be manure in the runoff from barnyards and feedlots (Wang et.al., 1996). Overall, the watershed and the streams in the watershed are ranked by the Department as a high priority with respect to non-point source pollution.

Date 2001

Watershed Trout StreamsWatershed Outstanding & Exceptional ResourcesLakes and Impoundments

Impaired Waters

List of Impaired Waters Monitoring & ProjectsProjects including grants, restoration work and studies shown below have occurred in this watershed. Click the links below to read through the text. While these are not an exhaustive list of activities, they provide insight into the management activities happening in this watershed.

Monitoring Studies

In the 1980�s the lower and middle Grant watersheds were subject to intense studies which resulted in a good appraisal of the watersheds. The studies showed the major impacts to streams to be reduced dissolved oxygen levels causing occasional fish-kills. Of secondary importance was habitat loss due to silt on the streambed filling in the pools. Diurnal oxygen variations during high flow events caused fish mortality. The low level oxygen was likely due to high levels of organic matter from manure entering the streams (WDNR, 1991). The Lower Grant River watershed was selected as Wisconsin non-point source abatement priority watershed project in 1989. The 10 year project was designed to enlist willing landowners in the watershed to install non-point source best management practices to protect water resources and improve farm conservation practices. The voluntary nature of the priority watershed project limited its success to some extent (WDNR, 2001).

Date 2012

Watershed RecommendationsMonitor biology on WBIC: 958100

Date

Status

Conduct biological (mIBI or fIBI) monitoring on Unnamed, WBIC: 958100, AU:5727230

5/21/2016

Proposed

Monitor biology on WBIC: 956400

Date

Status

Conduct biological (mIBI or fIBI) monitoring on Arrow Branch, WBIC: 956400, AU:13904

5/21/2016

Proposed

Re-Survey Muskellunge Creek

Date

Status

Water Quality staff should re-survey Muskellunge Creek for fish to re-evaluate the fish community.

1/15/2018

Proposed

Grant River TP

Date

Status

2013 TP "May Meet". AU 6901615, miles 34.87 - 39.67. Station 223214. If Clearly Meeting then potential for delisting.

5/1/2018

Proposed

Grant River TP

Date

Status

Category 5P. 2018 TP Results: May Meet. Station: 223214. AU: 6901615.

1/1/2018

Proposed

Snowden (Big Patch) Branch TMDL

Date

Status

The sediment TMDL was approved September 12, 2006.

5/1/2010

In Progress

Castle Rock & Gunderson Creek TMDL

Date

Status

The Castle Rock and Gunderson Creek TMDL was created to address phosphorus, sediment, and for at least one creek biological oxygen demand. The TMDL was approved and is in implementation through projects funded by the Clean Water Act Section 319 Program.

6/28/2004

In Progress

Watershed History Note

Watershed History NoteThe Lower Grant River Watershed in Grant County is home to a historical marker which marks the remains of Pleasant Ridge, a unique community of African American farmers. In 1848, when his owner died and gave him his freedom, Virginia slave Charles Shepard and his family moved to Wisconsin. They came with William Horner, nephew of the former owner, who hoped to prosper at lead mining. Horner soon discovered that lead mining was on its last legs, but he liked Wisconsin so much that he bought nearly 3,000 acres of rolling farmland.

Horner's freed slaves (Charles and Caroline Shepard, their three children Harriet, John and Mary, along with Charles' brother Isaac and his future wife, Sarah Brown) initially worked for him, but in only a few years the brothers Charles and Isaac had saved enough wages to purchase 200 acres and homesteads of their own. They called their hillside "Pleasant Ridge." Soon former slaves began to arrive from Tennessee, Missouri and Arkansas, and they, too, established farms in the vicinity.

Much of southwestern Wisconsin had originally been settled by white Southerners. Some, such as Governor Henry Dodge, were slave owners who brought slaves with them. But others had come north precisely to escape the slave labor system, which they opposed on religious or moral grounds. By 1850 a number of anti-slavery families and churches were well known, and one Grant County town was popularly called "Abolition Hollow." And by that time many of the original Southern settlers had been replaced by recent immigrants from Germany, England and Ireland who were intent on starting new lives. The original black settlers at Pleasant Ridge found life in Wisconsin much better than in the slave states where they'd grown up.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Pleasant Ridge contributed its share of soldiers. Though black recruits were initially prohibited by federal law, when that restriction was lifted in 1863, Charles Shepard and his son, John, both walked to Prairie du Chien to enlist in the Union Army. Charles was with the 50th U.S. Infantry Regiment and died at Vicksburg; John, a private in Company K, 42nd Regiment, died of disease at the end of the war, on his way home to Pleasant Ridge.

In the social chaos during and after the war, more Southern black families made their way into the rural Grant County settlement, which ultimately peaked at about 100 residents. In 1873, with their white neighbors, Pleasant Ridge residents built one of the first integrated schools in the nation; it accepted both black and white students and employed black as well as white teachers. Some of its pupils grew up to graduate from college and become teachers themselves. The white and black neighbors also created other facilities together, building the United Brethren Church in 1884 and a community hall in 1898.

Isaac Shepard became the most prosperous farmer in the region, and he and his nephew Ed Shepard lived well into their 90s. But as decades passed, it was hard to keep the young people down on the farm. Many left in search of greater social and economic opportunities in larger cities, such as Washington, D.C. The black population at Pleasant Ridge slowly declined throughout the 20th century until, in February 1959, Ollie Green Lewis, a descendant of the Green and Shepard families and the last black resident, died at Pleasant Ridge.

(Text and Photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society archives)

Date 2011