Ecological Landscapes

The Southern Lake Michigan Coastal Ecological Landscape is located in the southeastern corner of Wisconsin along Lake Michigan. The landforms in this Ecological Landscape are characteristic of glacial lake influence, with ridge and swale topography, clay bluffs, and lake plain along Lake Michigan. Further inland, ground moraine is the dominant landform. Soils typically have a silt-loam surface overlying loamy and clayey tills.

The historic vegetation in the northern part of this Ecological Landscape was dominated by sugar maple-basswood-beech forests with some oak while the southern part was dominated by oak forest, oak savanna and prairies. Wet, wet-mesic, and lake plain prairies were common in this area. Black ash and relict cedar and tamarack swamps were found in this Ecological Landscape. Today, most of the area is dominated by dairy and cash grain agriculture and intense urban development. Only about 8% of the Ecological Landscape is forested. Maple-beech forests are about half of the remaining forest types with the remainder split equally between oak-hickory and lowland hardwood forest types. There are some areas of wet-mesic and wet prairie but only small preserves remain since the landscape is heavily disturbed and fragmented. Because of this isolation, fragmentation, and high level of disturbance, non-native plants are abundant.

Existing Woodlands

According to year 2000 land use classifications, woodlands in the Des Plaines River watershed cover about 7.2 square miles, or about 5.4 percent of the total area of the watershed. Distributed in small stands throughout the watershed, these woodlands provide an attractive natural resource of immeasurable value. These woodlands accentuate the beauty of the stream system and the topography of the watershed and are essential to the maintenance of the overall quality of the environment in the watershed.

A demand for the conversion to urban uses of the remaining woodland areas within the watershed may be expected, especially for residential development. Real estate interests tend to acquire scenic woodland areas for such development, and this trend may be expected to accelerate. Severe damage to woodland areas has resulted where developers have subdivided woodland tracts into small urban lots and removed trees to develop subdivisions. Remaining trees are often seriously weakened through the loss of a large portion of the root system or compaction of the soils beneath the tree canopy. It is important to note that woodlands can be substantially preserved during land subdivision through careful construction practices and good subdivision layout and design. However, in the absence of good planning and plan implementation, there is no guarantee that such preservation will take place.

The overall quality of life within the watershed will be greatly influenced by the quality of the environment, as measured in terms of clean air, clean water, scenic beauty, and natural diversity. Woodlands contribute to clean air and water and to the maintenance of a diversity of plant and animal life in association with human life. The existing woodlands of the watershed, which required a century or more to develop, can be destroyed through mismanagement within a comparatively short period of time. Accordingly, careful attention should be given in the urban planning and development process to the preservation and proper management of the remaining woodlands of the Des Plaines River watershed as an important element of the natural resource base.

State Wildlife and Recreation Areas

Richard Bong State Recreation Area

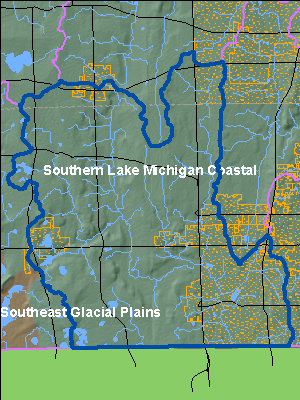

Once designated to be a jet fighter base, Richard Bong State Recreation Area is fittingly named after Major Richard I. Bong, a Poplar, Wisconsin, native who was America’s leading air ace during World War II. The project was abandoned three days before concrete was to be poured for a 12,500-foot runway. Local citizens had the foresight to protect this open space for future generations. In 1974, the state bought the land and it became the state’s first recreation area. The recreation area encompasses 4,515 acres of rolling grassland, savanna, wetlands, and scattered woodland. Most of it is in Wisconsin’s Southern Lake Michigan Coastal Ecological Landscape; a bit at the western edge is in the Southeast Glacial Plains.

Spring is a transition time at the recreation area and is the premier birding time. The earliest migrants, red-winged blackbirds, show up the end of February, but new winged visitors arrive throughout the spring: grackles, cowbirds, meadowlarks, killdeer, snipe, bluebirds, ducks, and swallows, each one in progression. Ducks and geese begin to nest in the area’s wetlands in March and April, and warblers pass through in May. Yellow-headed blackbirds, bobolink, and upland plovers are among the uncommon species seen here.

Spring is also the time when the air is filled with song -- chorus frogs, coyotes, song sparrows, cardinals, snipe, and others. The first green appears as the new leaves of spring wildflower show themselves. It’s a great time to bring the binoculars and hike the trails in search of the first signs of spring. It’s often windy, so it is a great place to bring a kite, with plenty of open space to fly it.

In the summer, the recreation area offers swimming at a sand beach, fishing, and picnicking at four different picnic areas. There are horseshoe and volleyball courts and a ball diamond. Skiing, sledding, and ice fishing are favorite winter sports.

A recreation area differs from a state park or forest in that it offers additional activities not traditionally found in state parks. Appropriate to its name, Richard Bong SRA offers an area where visitors may fly model airplanes, rockets, hang gliders, and hot air balloons. Richard Bong also has space to train both hunting and sled dogs, train falcons, ride all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and horses on trails, and hunt in season. All such activities take place in the special use zone or managed hunt areas.

Natural Areas and Critical Species Habitat Sites

An amendment to the regional natural areas and critical species habitat protection and management plan for Southeastern Wisconsin was completed by SEWRPC in 2010. The plan seeks to identify and protect what remains of the landscape of the region as it existed pre-European settlement. The plan also seeks to identify and protect other areas found to be vital to the maintenance of endangered, threatened, and rare plant and animal species. Both plan objectives foster biodiversity in the Region. Under the plan, natural areas are defined as tracts of land or water so little modified by human activity, or which have sufficiently recovered from the effects of such activity, that they contain intact native plant and animal communities believed to be representative of the pre-European-settlement landscape. Critical species habitats are defined as additional tracts of land or water which support endangered, threatened, or rare plant or animal species.

Natural areas, totaling 1,650 acres, were identified in the Des Plaines watershed. One six-acre natural area is protected under public ownership and one 27-acre natural area is protected under a private conservation ownership; two natural areas, totaling 418 acres, are protected under partial public and private ownership; one 413-acre natural area is protected under partial private, partial public, and partial private conservation ownership; and 15 natural areas, totaling 786 acres, are completely under unprotected private ownership. The 20 natural areas were identified, ranked according to their quality, and classified into one of the following three categories:

1. NA-1 Areas

NA-1 areas are native biotic communities of statewide significance that contain excellent examples of nearly complete and relatively undisturbed plant and animal communities that are believed to closely resemble those present during pre-European settlement times.

2. NA-2 Areas

NA-2 areas are native biotic communities that are judged to be of lower than NA-1 significance, perhaps on a county or regional basis. These areas are probably so designated because of evidence of a limited amount of human disturbance. They may also be of a high biotic quality, but of less than the minimum size necessary for an NA-1 ranking. In the future, some NA-2 sites may become of higher significance because of recovery from past disturbance, because of a sudden substantial decrease in the acreage of a once-common type, or after a more detailed inventory.

3. NA-3 Areas

NA-3 areas are native biotic communities substantially altered by human activities, but yet of local natural area significance. These sites often contain excellent wildlife habitat and also provide refuge for a large number of native plant species that no longer exist in the surrounding region because of land use activities.

Specifically, the classification of an area into one of the foregoing categories is based upon consideration of the diversity of plant and animal species and community types present; the expected structure and integrity of the native plant or animal community; the extent of disturbance from human activities, such as logging, grazing, water-level changes, and pollution; the commonness of the plant and animal communities present; any unique natural features within the area; and the size of the area.

One natural area within the Des Plaines River watershed was ranked NA-1; eight natural areas were ranked NA-2; and 11 natural areas were ranked NA-3. The total of 1,650 acres included within designated natural areas represents about 2 percent of the watershed.

Seven critical species habitat sites, totaling 1,522 acres, were identified within the Des Plaines watershed. Four of these sites, totaling 1,438 acres, are under public ownership, and three sites, totaling 84 acres, are under private ownership.

Environmental Corridors

SEWRPC has mapped the key elements of the natural resource base of the Southeastern Wisconsin Region, including lakes, streams, wetlands, woodlands, wildlife habitat areas, areas of rugged terrain, wet and poorly drained soils, and remnant prairies. In addition, SEWRPC has mapped such natural resource-related features as existing and potential park sites, sites of historic and archaeological value, areas possessing scenic vistas or viewpoints, and areas of scientific value. These inventories have resulted in the delineation of “environmental corridors,” which are broadly defined as

linear areas in the landscape containing concentrations of these significant natural resource and resource-related features. More information on environmental corridors can be found on SEWRPC’s website at http://www.sewrpc.org/SEWRPC/LandUse/EnvironmentalCorridors.htm.

The preservation of environmental corridors in essentially natural, open uses has many benefits, including flood-flow attenuation and water pollution abatement. Corridor preservation is important to the movement of wildlife and for the movement and dispersal of seeds for a variety of plant species.

Date 2012

Hydrologic Features

The Des Plaines River watershed may be considered as a composite of eight subwatersheds: 1) the Upper Des Plaines River subwatershed, 2) the Lower Des Plaines River subwatershed, 3) the Brighton Creek subwatershed, 4) the Center Creek subwatershed, 5) the Dutch Gap Canal subwatershed, 6) the Jerome Creek subwatershed, 7) the Kilbourn Road Ditch subwatershed, and 8) the Salem Branch of Brighton Creek subwatershed. For the hydrologic analyses performed, the watershed was divided into approximately 230 subbasins, ranging in size from 0.02 to 2.81 square miles, and having an average area of 0.61 square mile.

The surface-water resources of the Des Plaines River watershed consist of lakes, streams, and ponds. There are 18 lakes and ponds greater than two acres in area within the watershed, of which only six lakes are greater than 50 acres in area and are capable of supporting a variety of recreational uses. The total surface area of these six lakes is 635 acres, or less than 1 percent of the total watershed area. Ponds and other surface waters are present in even smaller proportions, totaling only 169 acres in area within the watershed. These lakes and smaller bodies of water provide residents of the watershed and persons from outside the watershed with a variety of aesthetic and recreational opportunities and also serve to stimulate the local economy by attracting recreational users.

Precipitation is the primary source of all water in the Des Plaines River watershed. Part of the precipitation runs directly off the land surface into stream channels and is ultimately discharged from the watershed; part is temporarily retained in snow packs, ponds, and depressions in the soil or on vegetation, and is subsequently transpired or evaporated; while the remainder is retained in the soil or passed through the soil into a zone of saturation or groundwater reservoir. Some water is retained in the groundwater system; but in the absence of groundwater development, much eventually returns to the surface through conveyance in agricultural drain tile systems or as seepage or spring discharge into ponds and surface channels. This discharge constitutes the entire natural flow of surface streams in the Des Plaines River watershed during extended periods of dry weather.

With the exception of the groundwater in the deep sandstone aquifer underlying the watershed, all of the water on the land surface and underlying the Des Plaines River basin generally remains an active part of the hydrologic system. In the deep aquifer, water is held in storage beneath the nearly impermeable water-tight Maquoketa shale formation and is, therefore, taken into the hydrologic cycle in only a very limited way. Since the recharge area of the deep aquifer lies entirely west of the Des Plaines River watershed, artificial movement through wells and minor amounts of leakage through the shale beds provide the only connection between this water and the surface water and shallow groundwater resources of the watershed.

Hydrologic Budget

Water in the deep sandstone aquifer under the Des Plaines watershed is taken into the hydrologic cycle in only a very limited way because there is little seepage through the relatively impermeable overlying Maquoketa shale. Because of this fact, a hydrologic budget for the Des Plaines River watershed can be developed considering only the surface and shallow groundwater supplies. In its simplest form, then, the long-term hydrologic budget for the Des Plaines River watershed may be expressed by the equation:

ET = P - R

where evaporation and transpiration have been combined into one variable, ET, denoting evapotranspiration, and where net groundwater flow out of the watershed has been assumed to be zero, as has the net change in the total surface and groundwater stored within the watershed. Because of seasonal variations in the behavior of the phases of the hydrologic cycle, this simplified equation is generally not valid for time durations of less than a year.

Based upon records from 1940 through 1993, the average annual precipitation over the watershed is 32.6 inches. Streamflow records collected from October 1, 1966, through September 30, 1994, at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) gaging station on the Des Plaines River at Russell, Illinois (Station Number 05527800) located just downstream of the Wisconsin-Illinois state line, indicate that the average annual discharge at that location is about 98.4 cubic feet per second (cfs), equivalent to 10.1 inches of water spread uniformly over the land surface of the watershed upstream from the gaging station. Substitution of these values for precipitation (P) and runoff R) into the simplified hydrologic budget equation indicates an average annual evapotranspiration of 22.5 inches. Therefore, on an average annual water-year basis, about 69 percent of the precipitation that falls on the Des Plaines River watershed is returned to the atmosphere by the evapotranspiration process, while the remaining 31 percent leaves the watershed as streamflow.

Seasonal Distribution of Peak Stages

Flood stages recorded at the U.S. Geological Survey Russell, Illinois gaging station on the Des Plaines River were used to evaluate the seasonal distribution of annual flood peaks. The seasonal distribution of the recorded peak discharges indicates that, over a 35-year record for the station as either a crest-stage or continuous recording gage, the occurrence of high water events was not limited to any one season. The lack of occurrence of annual peaks in the months of November, December and January is typical of watersheds in Southeastern Wisconsin. In the years from 1960 through 1994, the months of February, March, and April were the most active flood runoff periods in the Des Plaines River watershed, with 77 percent of the recorded annual peaks having occurred in these months.

The period February through April is a high runoff period in the watershed because of the effects of snow accumulation and frozen ground in February and March, and the effects of snowmelt and rainfall on near-saturated soils in March and April when the drying effects of transpiration are still minimal and when air and surface temperatures still inhibit evaporation.

Date 2012

Fisheries

In the 150 years of human activity which have reshaped the landscape along the Des Plaines River, portions of the River and some tributaries have been transformed from natural, meandering streams with a variety of habitats to modified, channelized streams with uniform conditions.

The fishery of the stream system has responded to these habitat changes primarily through a loss of overall diversity and particularly through a loss of species intolerant of the degraded water-quality conditions. Earliest fish records for the Des Plaines River came from two sites where collections were made in 1906 and 1928. Twenty-five species were found at these two stations, making an average of 12.5 species per station. Six of the 25 species were known to be intolerant of polluted conditions. Very intensive fish surveys carried out in 1979 and 1980 produced a total of 36 species at 39 stations, with five intolerant, 18 tolerant, and 13 very tolerant species. The average number of different species per station was slightly less than one. The 1994 survey yielded 30 species at 26 stations, with two intolerant, 16 tolerant, and 12 very tolerant species averaging slightly more than one species per station. No carp were found in either the 1906 or 1928 collection but were plentiful in recent decades.

The Des Plaines River clearly lacks the complement of fish normally occurring in natural waters. This loss of diversity and of intolerant species is due to a combination of factors:

1. The draining and filling of wetlands adjacent to the stream system, which has resulted in a loss of fish spawning, nursery, and feeding areas.

2. The ditching and realignment of stream channels, which has resulted in a uniform aquatic environment where there was once a great heterogeneity in the form of alternating riffles, pools, and runs. This ditching and realignment of the stream channels has resulted in uniform bottom types and water velocities which limit the types of fish that can normally inhabit a stream system and has thereby reduced the natural diversity.

3. Runoff from agricultural lands and construction sites, which transports sediment into the stream system, filling pools, covering gravel beds and plants, clogging the gills of fish and other aquatic animals, increasing turbidity, interfering with the mating and feeding behavior of fish, and, through abrasive action, sometimes injuring fish.

4. Fluctuations of water flow, which create alternating scouring and stagnant conditions within the stream system. Under low-flow conditions, fish become concentrated in shallow isolated pools where they are placed under great stress for lack of oxygen, food, and shelter. If these pools remain isolated into winter, they can freeze, killing all inhabitants. Since these pools may contain the entire breeding stock of a reach of stream, the future fishery is threatened when the fish in the pools are placed under stress or killed.

5. Runoff waters containing pesticides and fertilizers from urban and rural lands, sewage-treatment plant effluent, industrial discharges, and chemical spills, which have caused a decline in water-quality conditions.

6. The lack of instream vegetation and cover, which has prevented fish from finding shelter from predators and sudden floods. Some fish species may not carry on normal reproductive activities without proper cover. In addition, the lack of vegetative cover for other aquatic organisms may reduce the food resources available to fish, thereby affecting their growth and reproductive capacity.

As a result of these problems, the fish population of the Des Plaines River watershed has reached a point where the natural source of “seed stock” necessary to restore the depopulated areas of the watershed is apparently lacking. Very tolerant fish, such as black bullhead and carp, do well in the stream system; but intolerant species, such as certain shiners and daces, are lacking. Even such tolerant species as largemouth bass, northern pike, and bluegills would be more abundant in the Des Plaines River watershed if a balanced fishery were present.

Date 2011

River and Stream QualityAll Waters in WatershedAccording to the WDNR’s Register of Waterbodies (ROW) database, there are over 225 miles of streams and rivers in the Des Plaines River Watershed; 217 miles of which have been entered into the WDNR’s assessment database. Of these 217 miles, approximately 22% are meeting Fish and Aquatic Life uses and are specified as in “good” condition. The condition of the remaining stream miles is not known or documented.

Additional uses for which the waters are evaluated include Fish Consumption,

General Uses, Public Health and Welfare, and Recreation. These uses have not been directly assessed for the watershed. However, a general fish consumption advisory for potential presence of mercury is in place for all waters of the state.

One of the most interesting, variable, and, occasionally, unpredictable features of the watershed is its stream system, with its ever-changing, sometimes widely fluctuating, discharges and stages. The stream system of the watershed receives a relatively uniform flow of water from the shallow groundwater reservoir underlying the watershed. This groundwater discharge constitutes the base flow of the streams. Agricultural drain tiles also contribute to this base flow. The streams also periodically receive surface-water runoff from rainfall and snowmelt. This runoff, superimposed on the base flow, sometimes causes the streams to leave their channels and occupy the adjacent floodplains.

Perennial streams are here defined as those streams which maintain at least a small continuous flow throughout the year except under unusual drought conditions. Intermittent streams are those streams which do not maintain a continuous flow throughout the year in any case other than the exception noted in the above definition of perennial streams. There are 69.1 miles of perennial streams within the watershed.

Des Plaines River 2011

The source of the Des Plaines River is in the southwest one-quarter of U.S. Public Land Survey Section 33, Township 3 North, Range 21 East, in the Town of Yorkville, just north of the Racine-Kenosha county line and about 0.75 mile east of the Village of Union Grove. From its source, the River flows in a generally southerly direction for approximately 12.2 miles, to about the center of Section 16, Township 1 North, Range 21 East, in the Town of Bristol; then easterly for about four miles, to its confluence with the Kilbourn Road Ditch just east of IH 94-USH 41 in the Village of Pleasant Prairie; and finally southerly for approximately 5.6 miles, to the Wisconsin-Illinois state line. The River has a perennial stream length of about 20.5 miles. The river has also been found to be a wadable nursery water for smallmouth bass.

Salem Branch 2011

Salem Branch is a two-mile-long stream that fl ows out from Hooker Lake and discharges into Brighton Creek near the Village of Paddock Lake. It was last monitored in 2007 and the current use is listed as Fish and Aquatic Life with an attainable use as a warm water sport fishery.

Jerome Creek 2011

The origin of Jerome Creek is in the northeast one-quarter of Section 22, Township 1 North, Range 22 East, in the Village of Pleasant Prairie, just south of 93rd Street. The entire length of the Creek is in the Village of Pleasant Prairie. From its origin, the Creek flows about 0.7 mile in a generally northerly direction; then westerly for about 1.9 miles, crossing STH 31 and the Union Pacific Railroad line; then southwesterly for about two miles, to its confluence with the Des Plaines River one-quarter mile north of Kenosha County CTH Q. The Creek has a perennial stream length of about 1.7 miles.

Kilbourn Road Ditch 2011

The source of Kilbourn Road Ditch is located about one-half mile east of IH 94-USH 41 in the southwest one quarter of Section 30, Township 3 North, Range 22 East, Town of Mt. Pleasant, Racine County. From there, the stream flows southerly along IH 94-USH 41 for about 12.6 miles, to its confluence with the Des Plaines River in the southwest one-quarter of Section 7, Township 1 North, Range 22 East, in the Village of Pleasant Prairie. The entire length of the stream is classified as perennial.

Center Creek 2011

Center Creek, also known as Root River, has its origin on the one-quarter section line between the northeast and northwest one-quarters of Section 15, Township 2 North, Range 21 East, Town of Paris. From its origin it flows southerly for about 5.5 miles, to STH 50; then southeasterly for about two miles, to its confluence with the Des Plaines River, just west of IH 94-USH 41 in the southeast one-quarter of Section 12, Township 1 North, Range 21 East, Town of Bristol. The Creek has a perennial stream length of about 5.6 miles.

Brighton Creek 2011

The origin of Brighton Creek is in the northeast one-quarter of Section 14, Township 2 North, Range 20 East, Town of Brighton. From its origin, the Creek flows about six miles in a generally southerly direction, to its confluence with the Salem Branch of Brighton Creek in the southwest one-quarter of Section 6, Township 1 North, Range 21 East, Town of Bristol; then about three miles in a generally northeasterly direction, to its confluence with the Des Plaines River in the southwest one-quarter of Section 33, Township 2 North, Range 21 East. Brighton Creek has a perennial stream length of about nine miles.

Dutch Gap Canal 2011

The Dutch Gap Canal, which originates in the northeast one-quarter of Section 20, Township 1 North, Range 21 East, Town of Bristol, has a perennial stream length of 4.1 miles. The Canal flows in a generally southerly direction into Lake County, Illinois, where it is known as North Mill Creek and, farther downstream, as Mill Creek.

Date 2012

Watershed Trout StreamsWatershed Outstanding & Exceptional ResourcesLakes and Impoundments

The WDNR’s ROW database shows that there are over 313 acres of reservoirs and flowages and almost 837 acres of lakes, ponds, and other unspecifi ed open water in the Des Plaines River Watershed. Of these, approximately 1172 lake acres are entered into the state’s assessment database. Forty-three percent of these waters are indicated as supporting Fish and Aquatic Life use. A total of 667 acres have not been assessed for Fish and Aquatic Life use. Named lakes in the Des Plaines River Watershed include Lake Andrea, Paddock Lake, Hooker Lake, Lake Shangri-La, George Lake, Paasch Lake, River Oaks Lake, Mud Lake, Friendship Lake, Mud Turtle Pond, Bullfrog Pond, and Bass Pond. Reservoirs and flowages in

the watershed include Benet Lake, East Lake Flowage (Vern Wolf Lake) Montgomery Lake, League Lake, Juniper Lake, Paulin Pond, Bur Oak Lake, Pleasant Lake, and Barber Pond. The following water narratives summarize the most recent information available for the main lakes and flowages in the watershed.

Bur Oak Lake 2/1/82

This small, warm water impoundment is in Brightondale County Park. Water levels are controlled by a drop inlet control structure that can maintain a head of up to eight feet. Critical dissolved oxygen levels are reached in mid-winter and mid-summer. Fish species known to be present include bullheads, golden shiners, green sunfish, and fathead minnows. All of these have the ability to withstand low oxygen levels. Dense aquatic vegetation could also limit fish species. The lake provides wildlife habitat for waterfowl, shorebirds, and furbearers. Except for a state highway along its east side, it lies wholly within the county park and public access is available from there (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County Bur Oak Lake, T2N, R20E, Section 10, Surface Area 5.0 acres, Maximum Depth = 11.0 ft, Secchi disk = 1.0 ft).

Friendship Lake 2/1/82

This small, warm water drainage and seepage lake near the headwaters of Brighton Creek shows evidence of a large carp population that is causing extreme turbidity and reducing aquatic vegetation growth. The lake was chemically treated in 1963 under a private management permit to remove stunted bullheads, and then restocked with largemouth bass. It winterkilled in 1978. Fish species noted by a local landowner were northern pike, carp, and bullheads. Turbidity has reduced its habitat value for waterfowl and may also hinder the production of desirable fish. Recent surveys indicate that about half of its volume approaches critical levels of dissolved oxygen in mid-summer and winter. About 38 acres of wetland border the lake and provide excellent habitat for furbearers. Friendship Lake has an inlet and an outlet which flow ephemerally, usually in early spring each year. There is no public access except by navigating up its outlet from a state highway crossing (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County Friendship Lake, (Mud) T2N, R20E, Section 11, 12 Surface Acres = 11, Maximum Depth = 10.0 ft, Secchi disc = 1.0 ft.).

George Lake 2011

George Lake is located in the Town of Bristol in south central Kenosha County. Portions of the Towns of Bristol and Salem lie within the area tributary to George Lake. George Lake is a drained lake, having no continuously flowing inlet but with a flowing outlet, and, as such, is not primarily groundwater-fed but relies on precipitation and direct drainage from the surrounding land as the principal sources of its water. The mean depth of the Lake is about seven feet and the maximum depth is about 16 feet. George Lake has a volume of approximately 390 acre-feet, and a surface area of about 59 acres

The tributary area draining to the Lake is about 2,187 acres. Although it is a drained lake, it does have two intermittent inlets, both draining lands located to the west of the Lake and USH 45 in the Towns of Bristol and Salem: the first, located along the western shore of the Lake, drains a marsh and lowland area; the second, located along the southwestern shore of the Lake, drains a large marsh complex. George Lake is drained through an outlet located at the northeastern corner of the Lake that connects by way of a small unnamed stream to the Dutch Gap Canal, a tributary to the Des Plaines River. Water levels in George Lake are maintained by a small impoundment located at this outlet.

The Wisconsin Trophic State Index rating, as calculated from data taken by the Citizen Lake Volunteer Monitor on George Lake, classifies the lake as eutrophic.

George Lake supports a healthy and diverse aquatic plant community, with up to 11 different species of submerged aquatic plants within the lake. Of these species, two are considered invasive – Eurasian Water milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), and Curly-leaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus). Measures to control these invasive plants are conducted every year by the George Lake Rehabilitation District. These measures include herbicide and mechanical control.

George Lake supports a relatively large and diverse fish community. WDNR manages George Lake as a bass-panfish warmwater fishery. Fish surveys show Bluegill, Yellow perch, Pumpkinseed, Walleye, Largemouth bass, Carp, Northern Pike, White sucker, bullhead, Rock bass, crappie, and others.

Hooker Lake 2011

Hooker Lake is an 87-acre lake located in the Town of Salem in Kenosha County, and drains to the Salem Branch of Brighton Creek. The Wisconsin Trophic State Index, as calculated from data taken by the Citizen Lake Volunteer Monitor on Paddock Lake, classifies the lake as slightly eutrophic.

Hooker Lake supports a healthy and diverse aquatic plant community, though invasives such as Curly-leaf pondweed and Eurasian Watermilfoil are present. Measures to control the invasive plants, principally herbicidal control for EWM, are sponsored annually by the Hooker Lake Management District. Largemouth bass, Northern pike, Walleye and panfish are present in the lake. DNR owned wetland on the northern side of the lake provides habitat for northern pike.

Juniper Lake 2/1/82

This small impoundment in Brightondale County Park could be considered the headwaters of Brighton Creek. Its water level is controlled by a drop inlet control structure in the dam which maintains a head of 10 feet. Its intermittent outlet drains into Bur Oak Lake. It is managed for largemouth bass and panfish but since it is almost surrounded by a golf course, fishing is restricted during most of the open water season. Because of human activity, wildlife values are limited, but migrating waterfowl and shorebirds are common. Access is possible from Brightondale Park (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County Juniper Lake, T2N, R20E, Section 3, 6 Surface Acres = 12, Maximum Depth = 20 ft, Secchi disc = 7.0 ft).

Lake Andrea 2011

Lake Andrea is a former quarry in the Village of Pleasant Prairie, and is maintained as a public park and is intended for recreational use. The lake is 121 acres.

Lake Shangri-La (Benet Lake) 2011

Lake Shangrila and Benet Lake are located in the Towns of Bristol and Salem, Kenosha County, Wisconsin. A small portion of Benet Lake is located in the Town of Antioch in Lake County, Illinios. As a whole, the Shangrila-Benet Lake system has a surface area of 154 acres, a total volume of 748 acre-feet and a shoreline approximately 6.2 miles in total length. As a drained lake system, there is no inlet, but there is a more-or-less continuously flowing outlet, relying primarily on precipitation and runoff from the tributary area to supply the Lakes with water. Additional water inflow to the Lakes may be occurring from springs reported by residents to be present in the Lakes’ basins and from intermittent streams located along the southern and southwestern shoreline areas of Benet Lake that appear to transport snowmelt and surface runoff into the Lakes. Water flowing out of the system exits through a timber stop log spillway, which has a 13.2-foot-long crest, and which discharges to four 24-inch-diameter pipes set in an earthen dam, which was originally constructed in 1927 along the northeastern shore of Lake Shangrila. There is also a gated 24-inch-diameter corrugated metal pipe that can be used to provide additional hydraulic capacity. Outflowing water drains through a series of marshes and intermittent streams into the Dutch Gap Canal, a 4.1-mile-long waterway in Wisconsin which continues for about eight miles in Illinois where the waterway is called North Mill Creek. North Mill Creek then joins with Mill Creek, which flows another 4.5 miles to its confluence with the mainstem of the Des Plaines River near Wadsworth in Lake County, Illinois. The lake system today constitutes a heavily used, recreational water resource and residential community situated within easy reach of the Milwaukee metropolitan area, and is a popular destination for weekend recreational users, as well as year-round residents.

Secchi-disk data for Lake Shangrila indicated a TSI of 69, while Secchi-disk data, and chlorophyll-a and total phosphorus concentrations for Benet Lake indicate a TSI of 67. Both values are consistent with eutrophic conditions. A value above 50 is generally indicative of the enriched conditions associated with eutrophic lakes.

The aquatic plant communities observed during 2008 in the Lake Shangrila-Benet Lake system had limited biodiversity, with eight species recorded during the survey. any lakes in the Region have a dozen or more species of aquatic plants. In comparison with these lakes, the Lake Shangrila-Benet Lake system has an impoverished aquatic plant flora, which limits the ability of these lakes to sustain fish and aquatic life and associated human uses, especially given that two of the observed aquatic plant species are declared nuisance species identified in Chapter NR 109 of the Wisconsin Administrative Code. A reduced species diversity is consistent with the enriched trophic states of the Lakes.

Lakes Shangri-la and Benet support a large and diverse fish community. Fish surveys report Bluegill, Yellow perch, Pumpkinseed, Walleye, Largemouth bass, Carp, Northern Pike, White sucker, bullhead, Rock bass, Channel catfish, and Black crappie.

League Lake 2/1/82

This is a small warm water seepage lake lying wholly within lands owned by the Union League Foundation. Water levels are controlled somewhat by a low-head splashboard type structure on its outlet. The lake’s outlet flows only during the spring runoff or after periods of excessive rainfall. Softstem bulrushes, cattails, and white water lilies along its shoreline provide ideal resting and feeding habitat for fish, waterfowl, and furbearers. The land in the immediate watershed is woods, marsh, and open grass. Fish consist of largemouth bass, yellow perch, crappies, bluegills, and bullheads. There is no public access (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County League Lake, T2N, R20E, Section 35 Surface Acres = 14.4, Maximum Depth = 22.0 ft, Secchi disc = 3.0 ft).

Montgomery Lake 2011

Montgomery Lake is a 46-acre lake, draining to the Salem Branch of Brighton Creek. This warm water seepage lake is part of the headwaters of Salem Branch and Brighton Creek. Its entire shoreline is bordered with cattail marsh, giving it exceptional value for wildlife. The marshlands also provide spawning habitat for game fish like northern pike. The general ecology of

the lake depends on these marshlands. Unfortunately, its shallow depth and high percentage of organics make it subject to winterkill. Records indicate that a significant winterkill occurs at least once every 10 years.

The Wisconsin Trophic State Index, as calculated from historical data taken by the Citizen Lake Volunteer Monitor on Montgomery Lake, classifies the lake as borderline mesotrophic/eutrophic. Aquatic plant diversity is very high on Montgomery Lake. Water clarity is very good, promoting a healthy population of native plants. While some aquatic invasives are present, they are not at significant enough density to warrant either mechanical or herbicidal control. Practically the entire shoreline is bordered by cattails, providing wildlife habitat and acting as a buffer to protect water quality. Principal fish in Montgomery Lake include Largemouth bass, crappies, perch, bluegills, and bullhead.

Mud Lake 2/1/82

Although this small, cattail fringed lake is adjacent to a subdivision, there are no developments on its marshy shores. The predominant bottom type is muck and it is subject to winterkill when water levels are low and the winter severe. From past records, it can be expected to winterkill at least once every 10 years. Mud Lake receives drainage from a man-made lake to the southwest. Wetlands adjoin it on all sides, but the watershed is mostly cultivated agricultural land. The lake provides good habitat for waterfowl and furbearers, such as muskrats and raccoons. Waterfowl hunting is common. During high water periods, fish species migrate up from the Dutch Gap Canal to populate the lake. Northern pike, largemouth bass, and various panfish are normally present in the fishery. The lake is surrounded by private lands and there is no public access (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County Mud Lake, TlN, R21E, Section 32 Surface Acres = 22.0 ft. Maximum Depth = 15.0 ft, Secchi disc = 4 ft).

Paasch Lake 2/1/82

This small, warm water seepage and drainage lake is almost completely bordered by cattail marsh. There is also a ring of white and yellow water lilies growing out to a depth of five feet. Winterkill is possible during severe winters. A large carp population causes extreme turbidity and gives the lake’s waters a mucky appearance. The lake has wildlife habitat value for waterfowl and marshland furbearers in the 56 acres of wetland that adjourn it. Presently, only three dwellings are located near the lake and there is no public access (Source: 1982, Surface Water Resources of Kenosha County Paasch Lake, TlN, R21E, Section 29, 30 Surface Acres = 21, Maximum Depth = 20 ft, Secchi disc = 2.5 ft).

Paddock Lake 2011

Paddock Lake is a 112-acre lake located in the Village of Paddock Lake in Kenosha County. The lake drains to the Salem Branch of Brighton Creek. Maximum depth of the lake is 32 feet.

The Wisconsin Trophic State Index, as calculated from data taken by the Citizen Lake Volunteer Monitor on Paddock Lake, classifies the lake as slightly eutrophic. Paddock Lake supports a healthy and diverse aquatic plant community, with over 23 species of submerged or emergent aquatic plants. Management of invasive plants and for navigation is done by a harvester program, operating under permit from WDNR. Largemouth bass, Northern pike, Perch, and panfish are present in the lake.

Vern Wolf Lake 2011

Vern Wolf Lake (formerly East Lake Flowage) is a 123-acre lake located within the Bong State Recreational Area in the Town of Brighton in Kenosha County. The lake drains to Brighton Creek. The Wisconsin Trophic State Index, as calculated from data taken on Vern Wolf Lake, classifies the lake as slightly eutrophic. Aquatic plant diversity in the lake is good, with the lake supporting dense growth of aquatic plants. No management for aquatic plants takes place on the lake.

Date 2012

Wetland Health

Wetland Status:

The Des Plaines River Watershed is located in Kenosha and Racine counties. Roughly six percent of the current land uses in the watershed are wetlands. About one-quarter of the original wetlands in the watershed are estimated to exist. Of these wetlands, the majority include forested wetlands (25%), and emergent wetlands (52%), which include marshes and wet meadows.

Wetland Condition:

Little is known about the condition of the remaining wetlands but estimates of reed canary grass (RCG) infestations, an opportunistic aquatic invasive wetland plant, into different wetland types has been estimated based on satellite imagery. This information shows that reed canary grass dominates 23% of the existing emergent wetlands, and 11% of the remaining forested wetlands. Reed Canary Grass domination inhibits successful establishment of native wetland species.

Wetland Restorability:

Of the 15,667 acres of estimated lost wetlands in the watershed, approximately 71% are considered potentially restorable based on modeled data, including soil types, land use and land cover (Chris Smith, DNR, 2009).

Existing Wetlands

Wetland vegetation typically includes sedges, rushes, cat tails, red-osier dogwoods, and willows. Wetlands within the Des Plaines River watershed include deep and shallow marshes, southern sedge meadows, fresh (wet) meadows, wet prairies, shrub-carrs, and southern wet to wet-mesic lowland hardwood acres. Based on SEWRPC’s year 2000 land use inventory, wetlands in the watershed currently cover about 11.4 square miles (8.6%) of the total area of the watershed

Water and wetland areas probably constitute the most important landscape feature within the watershed and can serve to enhance all proximate uses. Their contribution to resource conservation and recreation within the watershed is immeasurable. Recognizing the desirable attributes of wetland areas, continued efforts should be made to protect this resource by discouraging wetland draining, filling, and conversion to incompatible agricultural and urban uses, all costly, both in monetary and environmental terms. Wetlands have an important set of common natural functions that make them ecologically and environmentally valuable resources.

Wetlands affect the quality of water. Aquatic plants change such inorganic nutrients as phosphorus and nitrogen into organic material, storing it in their leaves or in peat, which is composed of plant remains. The stems, leaves, and roots of these plants also slow the flow of water through a wetland, allowing the silt and other sediment to settle out. Wetlands thus help to protect downstream water resources from siltation and pollution. Wetlands influence the quantity of water. They act to retain water during dry periods and to hold it back during wet weather, thereby stabilizing stream flows and controlling flooding. At a depth of 12 inches, an acre of marsh is capable of holding more than 325,000 gallons of water; it thus helps protect communities against flooding. Wetlands may serve as groundwater recharge and discharge areas.

Date 2012

Aquatic Invasive Species

Curly-leaf pondweed, Eurasian water-milfoil, rusty crayfish, and zebra mussel have all been verified and vouchered in Des Plaines River Watershed waterbodies. The table below summarizes the locations where these Aquatic Invasive Species have been observed and when their presence was first confirmed.

Date 2011

Fish Consumption Advice

No specific fish consumption advisories are issued for waterbodies within the Des Plaines River Watershed at this time. However, a general fish consumption advisory for potential presence of mercury is in place for all waters of the state.

Date 2011

Groundwater

The Des Plaines River watershed is richly endowed with groundwater resources. In the rural portions of the watershed, the domestic water supply is provided by the groundwater reservoir. Lake Michigan is the source of the public water supply provided to the City of Kenosha and Village of Pleasant Prairie.

Rock units that yield water in usable amounts to pumped wells and in significant amounts to lakes and streams are called aquifers. The aquifers beneath the watershed differ widely in water-yield capabilities and extend to great depths, probably attaining a thickness in excess of 1,500 feet in portions of the watershed. There are three major aquifers underlying the Des Plaines River watershed. These are, in order from land surface downward, as follows: 1) the sand and gravel deposits in the glacial drift; 2) the Niagara aquifer, the shallow dolomite strata in the underlying bedrock; and 3) the Cambrian and Ordovician strata, composed of sandstone, dolomite, and shale. Because of their relative nearness to the land surface, the first two aquifers are sometimes called the “shallow aquifers” and the third aquifer, the “deep aquifer.” Wells tapping these aquifers are referred to as “shallow” or “deep” wells, respectively. Gradual discharge from the sand-and-gravel aquifer is the primary source of base flow to the Des Plaines River and the other streams and lakes in the watershed.

Recharge to the sand-and-gravel aquifer occurs primarily through infiltration of precipitation that falls on the land surface directly overlying the aquifer. Within the watershed, the rate of recharge to the sand-and-gravel aquifer is relatively slow because of the presence of overlying glacial till of low permeability.

Recharge to the Niagara aquifer occurs primarily through infiltration of precipitation that seeps through the glacial drift above the aquifer. As with the sand-and-gravel aquifer, the rate of recharge is limited by the relatively low permeability of the glacial drift. Some additional recharge to the Niagara aquifer occurs as lateral subsurface inflow from the west.

Recharge to the sandstone aquifer, located in the Cambrian and Ordovician strata, occurs in the following three ways: 1) seepage through the relatively impermeable Maquoketa shale, 2) subsurface inflow from natural recharge areas located to the west in Walworth County, and 3) seepage from wells that are hydraulically connected to both the Niagara and the sandstone aquifers. Although the natural gradient of groundwater movement within the sandstone aquifer is from west to east, concentrated pumping in the Chicago area has created a southeasterly gradient.

Springs are areas of concentrated discharge of groundwater at the land surface. Alone, or in conjunction with numerous smaller seeps, they may provide the source of base flow for streams and serve as a source of water for lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Conversely, under certain conditions, streams, lakes, ponds, and wetlands may be sources of recharge that create springs. The magnitude of discharge from a spring is a function of several factors, including the amount of precipitation falling on the land surface, the occurrence and extent of recharge areas of relatively high permeability, and the existence of geologic and topographical conditions favorable to discharge of groundwater to the land surface.

The following groundwater information is for Kenosha County (from Protecting Wisconsin’s Groundwater through Comprehensive Planning website, http://wi.water.usgs.gov/gwcomp/), which roughly approximates to the Des Plaines River Watershed.

Two of five municipal water systems in Kenosha County have a wellhead protection plan: Bristol and Paddock Lake, which are both located within the Des Plaines River Watershed. However, none of the five have a wellhead protection ordinance and the county has not adopted an animal waste management ordinance.

From 1979 to 2005, total water use in Kenosha County has fluctuated from about 17.8 million gallons per day to 23.0 million gallons per day. The fluctuations in total water use are due primarily to fluctuations in public use and loss, industrial, and domestic uses. Commercial use increased during the same period. The proportion of county water use supplied by groundwater has fluctuated from about 11% to 18% during the period 1979 to 2005.

Private Wells

Ninety-two percent of 91 private well samples collected in Kenosha County from 1990 through 2006 met the health-based drinking water limit for nitrate-nitrogen. Land use affects nitrate concentrations in groundwater. An analysis of over 35,000 Wisconsin drinking water samples found that drinking water from private wells was three times more likely to be unsafe to drink due to high nitrate in agricultural areas than in forested areas. High nitrate levels were also more common in sandy areas where the soil is more permeable. In Wisconsin’s groundwater, 80% of nitrate inputs originate from manure spreading, agricultural fertilizers, and legume cropping systems.

A 2002 study estimated that 21% of private drinking water wells in the region of Wisconsin that includes Kenosha County contained a detectable level of an herbicide or herbicide metabolite. Pesticides occur in groundwater more commonly in agricultural regions, but can occur anywhere pesticides are stored or applied. There are no atrazine prohibition areas in Kenosha County. One hundred percent of five private well samples collected in Kenosha County met the health standard for arsenic.

Potential Sources of Contamination

Pheasant Run Recycling & Disposal operates the one licensed landfill in the Des Plaines River Watershed in the town of Paris. There are no Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) or Superfund sites in the watershed.

WDNR’s Remediation and Redevelopment (RR) Program oversees the investigation and cleanup of environmental contamination and the redevelopment of contaminated properties. The RR Program provides information about contaminated properties and other activities related to the investigation and cleanup of contaminated soil or groundwater in Wisconsin through its Bureau for Remediation and Redevelopment Tracking System (BRRTS) database (WDNR 2010e).

The database shows that there are 215 sites in Kenosha County that are classified as “open”, meaning “contamination has affected soil, groundwater, or more and the environmental investigation and cleanup need to begin or are underway.” These sites include 51 Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) sites, 73 Environmental Repair (ERP) sites, 83 spill sites, and eight Voluntary Party Liability Exemption (VPLE) sites.

The Petroleum Environmental Cleanup Fund Award (PECFA) program was created in response to enactment of federal regulations requiring release prevention from underground storage tanks and cleanup of existing contamination from those tanks. PECFA is a reimbursement program returning a portion of incurred remedial cleanup costs to owners of eligible petroleum product systems, including home heating oil systems. As of May 31, 2007, $34,684,091 has been reimbursed by the PECFA program to clean up 236 petroleum-contaminated sites in Kenosha County. This equates to $214 per county resident, which is less than the statewide average of $264 per resident.

Date 2012

Impaired Waters

List of Impaired Waters

Goals

1/4/2012

Increase awareness of watershed stewardship within the watershed through multiple outreach and education activities.

1/4/2012

Work with local communities and other governmental bodies to encourage preservation and identification of sensitive woodlands to preserve these areas in the atershed.

1/4/2012

Work with local communities to reduce polluting runoff and encourage wellhead protection ordinances.

Priorities

10/17/2011

Highway runoff contributes sediment, nutrients, and pollutants to local waterways.

10/17/2011

There is a lack of adequate stream buffers in portions of the watershed.

10/17/2011

The potential impact of farm tiles to stream water quality is not well understood.

10/17/2011

Fish passage barriers prevent passage of fish species to historic spawning or nursery areas.

10/17/2011

Lack of inventory and monitoring data limits ability to identify source control areas and to classify the waterways and determine if they should be added to the EPA 303(d) list of impaired waterways.

10/17/2011

Runoff from developed (and developing) areas has a significant negative impact to water quality through the introduction of sediment, nutrients, and other pollutants to nearby waterways.

10/17/2011

Loss of wetlands and woodlands in the watershed has resulted in the loss of valuable fish & wildlife habitat, plus other potential benefits, such as filtering pollutants, maintaining summer base flow, alleviating flooding concerns, and reducing water temperatures.

10/17/2011

Lack of awareness, understanding and participation in watershed stewardship.

10/17/2011

Aquatic invasive species are present and can have negative impacts on native species.

10/17/2011

Extensive ditching has reduced in-stream habitat quality.

10/17/2011

In-stream warm-water fish habitat needs improvement.

10/17/2011

Sedimentation from bank erosion and agricultural fields impacts water quality and available habitat.

1/4/2012

The historic loss of 75% of wetlands in the watershed is a pressing issue for this area.

1/4/2012

Need for wellhead protection ordinances in watershed communities due to potential complex groundwater, drinking water issues in the area.

1/4/2012

The historic and current disappearance of woodlands due to development throughout the watershed has had a major impact on the ecological diversity and complexity of this watershed.